Why Most ‘Disruptors’ Aren’t Actually Disrupting Anything

In the guessing game of who will sink and who will swim, understanding disruptive innovation can be your life jacket.

Iftech startup giants in the likes of Uber and Tesla Motors come to mind at the mention of the term disruptive innovation, you’re dead wrong. You are also not alone.

In fact,the theory of disruption has become so widely misunderstood that the very man who invented it, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, recently felt the need to clarify the common misconceptions in the Harvard Business Review. Twenty years after the coining of the

In fact,the theory of disruption has become so widely misunderstood that the very man who invented it, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, recently felt the need to clarify the common misconceptions in the Harvard Business Review. Twenty years after the coining of theA key concern identified was that the majority of persons speaking of ‘disruption’ had not been exposed to a serious article or book on the topic, resulting in a commonplace association with innovation and a usage of the term to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and previously successful incumbents stumble. Such an overapplication of the theory undermines its usefulness.

The Three Main Types of Innovation

In order to fully understand the limits of disruptive innovation, one must comprehend its academic context within the field of business administration. Effectively, three main types of innovation exist: sustaining innovation, low-end disruptive innovation and new-market disruptive innovation. No new technology is intrinsically sustaining or disruptive: instead, this is determined by how it is deployed in the market place relative to the business models for existing products and services. Disruption must thereby be used as a relative term, since a business may only be disruptive relative to an existing product or business model.

Most disruptive innovations are a mixture of low-end and new-market disruptive innovations.

Most disruptive innovations are a mixture of low-end and new-market disruptive innovations.Sustaining innovation, first of all, is concerned with providing ever better products that can be sold for ever better profits to an incumbent’s very best customers. Since it is focused on improving the products and services for a company’s most demanding customers, Most disruptive innovations are a mixture of low-end and new-market disruptive

innovations.

it effectively improves or sustainsprofit margins by exploiting the existing processes and cost structure as well as by better employing the current competitive advantages.

Low-end disruptive innovation, on the other hand, takes advantage of markets in which existing products offer more performance than many customers want or need. By focusing on the over-served customers in the low-end of the mainstream market, entrants utilize a new operating or financial approach to earn attractive returns at discount prices required to win businesses at the low-end of the market, typically as incumbents focus on sustainable innovation.

Last of all, the term new-market disruptive innovation describes a process whereby smaller companies with fewer resources are able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses by creating a new market and effectively enticing the incumbents’ customers into it. Entrants target non-consuming customers who previously lacked the money or skill to buy or use the product by employing a business model that makes money at a lower price per unit sold, and at unit production volumes that initially will be small.

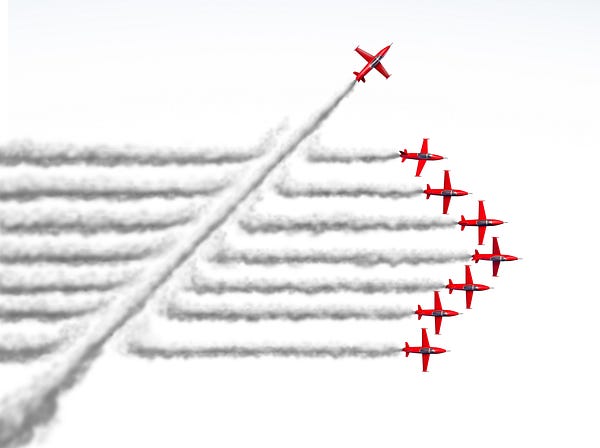

All disruptors are innovators, but not all innovators are disruptive.

Thus, one can discern that all disruptors are innovators, but not all innovators are disruptive. It is also worth noting that the line between low-end and new-market disruption innovation oftentimes becomes blurred. Most disruptive innovations can easily be classified into both categories and it is, in fact, much rarer for an innovating entrant to fall solely into one designation.

Disruptive Innovation’s Modus Operandi

Both types of disruptive innovation, low-end and new-market, are ultimately described as ‘disruptive’ due to the threatening consequences of their modus operandi: incumbents’ mainstream customers slowly beginning to convert to the entrants’ products and services.

Disruptive innovators are threatening due to their modus operandi.

Disruptive innovators are threatening due to their modus operandi.A typical blend of low-end/new-market disruptors enters the market with new or innovative technologies, using it to deliver products or services better suited to the incumbents’ overlooked customers at a lower price, before steadily ascending upmarket to eventually deliver a performance

Disruptive innovators are threatening due to their modus operandi.

equivalent to that of the established incumbent businesses. Due to the entrants’ advantage of innovative technology — allowing for new or innovative products or services at a lower price — customers are inherently drawn to them. Case in point: the infamous tale of Blockbuster and Netflix.

As per Christensen, disruptive innovation’s modus operandi leads to drastic upheavals not because established businesses do not innovate — they do — but because they’re focused on sustaining innovation instead. It makes sense for incumbents to focus on the latter, since it focuses on the most profitable customers where profit margins are highest, but in doing so they inevitably leave the door open for innovative disruptors.

Uber and Tesla Motors: Innovators Not Disruptors

Considering the eternal entrepreneurial quest for the next big idea, a door left ajar represents just the type of an opportunity your average businessman going solo is hunting for.

This was the reasoning that allowed for “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Christensen’s entrepreneurial Bible published in 1997, to gain iconic status and for entrepreneurs worldwide, particularly in Silicon Valley, to latch onto the term in a manner that has been describe as ‘obsessive’. It is understandable, then, that many Valley devotees may not be pleased to hear that numerous members of the Billion Dollar Startup List are undeserving of their titles as beacons of disruptive innovation.

Alas, according to the father of the theory of disruption himself, “financial and strategic achievements do not qualify the company as genuinely disruptive”.

Uber, a company thoroughly transforming the taxi business in the United States, is not truly disrupting it. Tesla Motors, Elon Musk’s brainchild innovating the electric car Numerous “disruptors” are undeserving of their titles as beacons of disruptive

innovation.

industry, is not a disruptor either. The reasoning behind this may be succinctly summarized in two key statements of fact: first, disruptive innovations originate in low-end or new-market footholds, and second, disruptive innovations don’t catch on with mainstream customers until quality catches up to their standards.

Financial and strategic achievements do not qualify the company as genuinely disruptive.

Our two case studies at hand fall outside the bounds of both requirements. Uber originated in neither of the aforementioned footholds, since taxi services were neither a new opportunity nor a low-end market. As per Clayton Christensen, “disrupters start by appealing to the low-end or unserved consumers and then migrate to the mainstream market. Uber has gone in exactly the opposite direction: building a position in the mainstream market first and subsequently appealing to historically overlooked segments.”

Simultaneously, Uber’s service, whilst generally slightly cheaper, has also never been considered inferior as is characteristic of disruptive innovators. Consumers have been historically unwilling to switch to a new offering merely due to its lower price and instead wait until the quality rises so as to satisfy them. No such waiting was ever required of Uber, whose service is sometimes described as better than those of traditional taxi companies.

Tesla Motors’ divergence from a typical disruptive innovation is even more salient. Unlike all disruptive businesses, the company originated at the top end of the automobile market and is only now, with its Model 3, aiming to sell its affordable electric car to the mainstream consumers. Most elements of Uber and Tesla Motors’ strategy — from cashless, safe and convenient ride-hailing to innovative, sustainable car design — appear to be those of a sustaining innovation.

Why Does the Distinction Matter?

The distinction between disruptive innovators and their mislabeled counterparts is more important than you think.

The distinction between disruptive innovators and their mislabeled counterparts is more important than you think.To illustrate the gravity of this argument, consider Netflix’s notorious overtake of Blockbuster in the entertainment industry. The former, by initially focusing on a select inferior market

Netflix’s model of “hallmark disruption” allowed for their infamous decimation of

Blockbuster in the entertainment industry.

composed of “movie buffs who didn’t care about new releases, early adopters of DVD players, and online shoppers”, represented what has been described as a hallmark of disruption before eventually moving upmarket and utterly crushing what used to be an infinitely stronger competitor. So small as to be utterly overlooked, Netflix exploited its innovative edge — as well as the monumental rise of online streaming — and inflicted a seismic wound on the home video market. Other high-profile examples of disruptive business models in practice include Apple’s mobile ecosystem connecting application developers with smartphone users (not the iPhone per se, but the formation of the subsequent platform that established smartphones as primary means of internet access, thereby disrupting the laptop market) as well as alternative finance entrants in the likes of equity crowdfunding platforms, like StartEngine, which supersede traditional banking by directly connecting investors with firms.

Disruption theory teaches us that whilst incumbents usually win sustaining battles; entrants tend to win disrupting battles.

Disruption theory teaches us that whilst incumbents usually win sustaining battles; entrants tend to win disrupting battles. Whilst disruption is an opportunity long before it is a threat, failing to notice true innovative disruption might very well be an end of a business — if not an industry. Although not every disruptive path leads to success, and disruption theory

an industry entrant.

cannot claim to explain everything about innovation or business success, empirical tests have shown that using disruptive theory allows for measurably and significantly more accurate predictions of which fledgling businesses will succeed. True disruptive innovation is admittedly difficult to identify, and surprisingly rare, but companies on such a trajectory can pose a mortal threat. The effect of mere innovators, on the other hand, is not as drastic.

Key Takeaways

As the entertainment industry has taught us, true disruptive innovation is a threat to behold.

“Lights…Camera…Disruption”, indeed.

The ability to distinguish between the different types of innovation — sustaining, low-end and new-market — can allow one to spot a genuine disruptor from a wrongfully labeled innovator, thus permitting for anticipation of industry-threatening behavior and the spotting of disruption in its early stages. It might allow an investor to discern a remarkable investing opportunity from yet another startup destined for mediocrity.

In the guessing game of who will sink and who will swim, understanding disruptive innovation can be your life jacket.